What Muscles Does Cycling Work? From Core to Calves

Cycling is a popular form of exercise that has many benefits for physical and mental health, and it continues to grow in popularity in outdoor and indoor settings.

Most people know cycling is a potent form of cardiovascular exercise, but the powerful muscular benefits don’t receive as much attention.

So, what muscles does cycling work?

Well, this article will discuss all of the major muscle groups it strengthens, followed by a selection of the best strength exercises and stretches for those muscles.

Effects of Cycling on Body Shape

Among cycling’s numerous benefits is its effect on body shape.

Regular cycling alongside good nutrition and dietary habits will typically result in weight loss and recomposition faster than walking. Recomposition is a change in the ratio of muscle and fat.

Cycling is one of the most effective types of cardio workouts that uses a significant amount of fat as fuel, reducing body fat. In addition, with appropriate nutrition pre and post-ride, your body builds muscle. Most of this muscle is in the lower body, including the quads, hamstrings, lower leg muscles, and glutes.

As a result, cycling impacts body shape by slimming and toning the upper body and waist while simultaneously growing and toning the muscles in the lower legs.

However, for most recreational cyclists, muscle growth in the legs is limited, and most of the perceived change comes from reducing fat to expose the muscle (toning).

What Muscles Does Cycling Work?

Again, cycling primarily works the muscles in the lower body.

At each stage of the pedal stroke, you recruit the muscles in different amounts, with some, like the quads, working more overall.

Cycling discipline, type of bike, biking style, terrain, and bike fit are some factors that influence which muscles work and how much they work.

For example, a road rider in an aggressive position will utilize the glutes more than a mountain biker in an upright position.

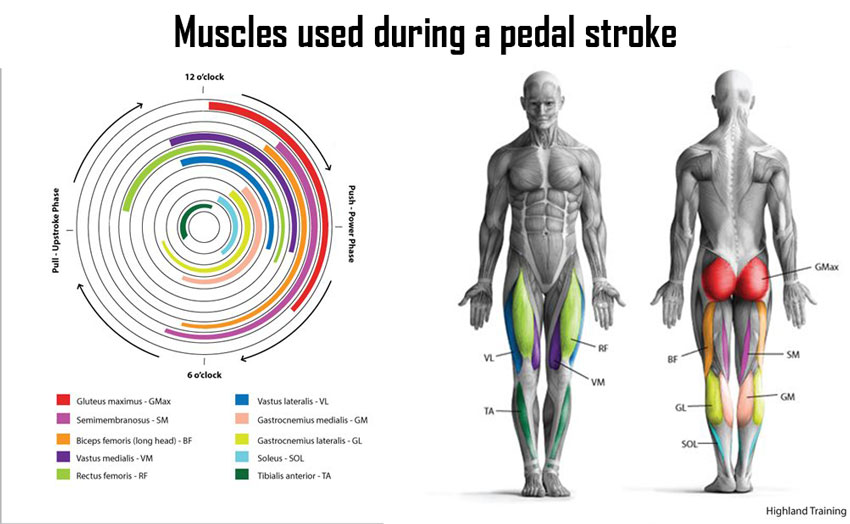

This illustration shows which muscles are active during specific parts of a pedal stroke. | Image source: trainingpeaks.com

To visualize how the individual muscles of the leg contribute to the pedal stroke, it helps to consider each revolution as a clock face, with the individual muscles engaging for a specific length of time.

The pedal stroke is typically broken down into two phases, power (push) from 12 to 6 o’clock and recovery (upstroke) from 6 to 12.

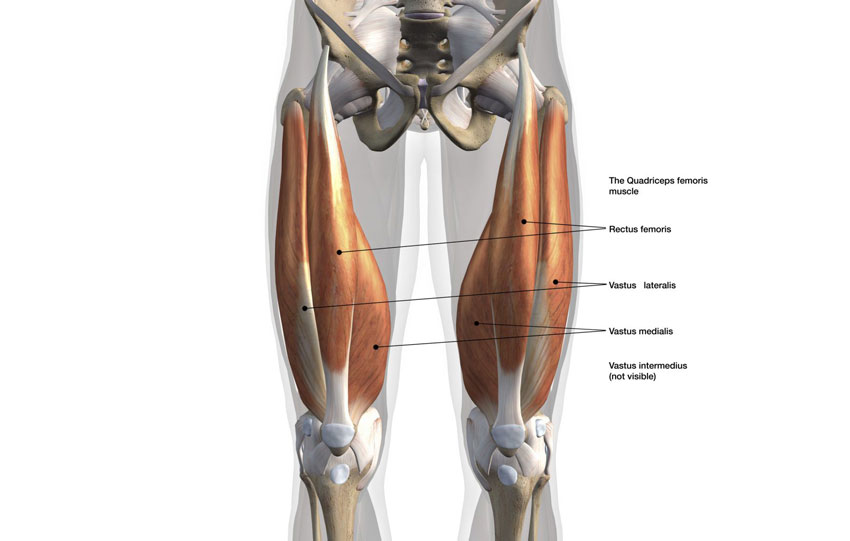

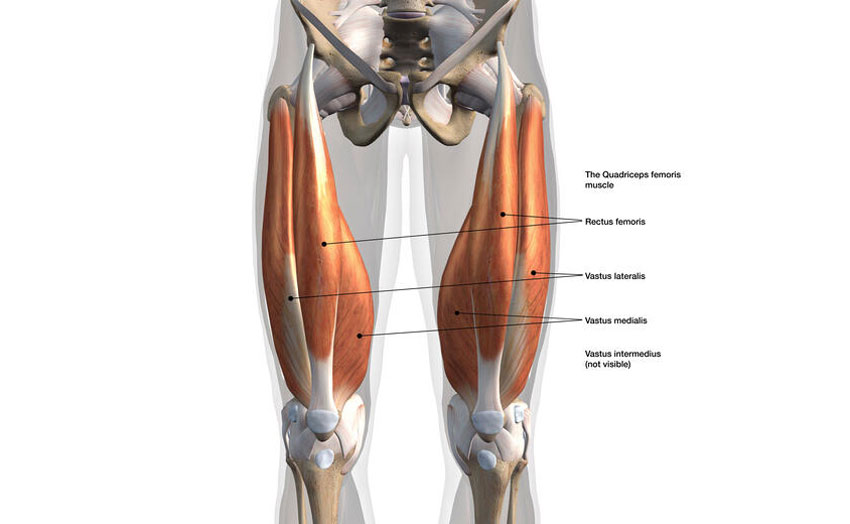

Quads

There are four quadriceps muscles in total, the rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius. A primary function of these muscles is to bend the hip.

The rectus femoris is the largest quadriceps muscle and the most active of the four while cycling, generating power from 10 to 6 o’clock.

The vastus lateralis and medialis activate just before the pushing phase of the pedal stroke, slightly after the rectus femoris at 11/12 o’clock.

These muscles contribute the highest percentage of power generated while cycling, somewhere in the region of 40%, which will change based on the factors we listed earlier.

In addition, clipless pedals can impact when a muscle begins to work, recruiting the rectus femoris earlier than flat pedals.

Strengthening the quadriceps muscles off the bike significantly increases the amount of power you can generate while riding.

Hamstrings

The hamstrings comprise three main muscles, the biceps femoris, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus. One of the primary jobs of the hamstrings is to flex the knee.

These muscles activate during the power phase of the pedal stroke at around 2 or 3 o’clock and continue to roughly 8 o’clock.

Although highly active while cycling, the hamstrings contribute a small percentage of the power generated on a bike, in the region of 10%.

The hamstrings are one of the muscle groups, along with the hips, that shortens from riding regularly and sitting often. As a result, they benefit a lot from post-ride stretching.

Gluteus Muscles (Glutei)

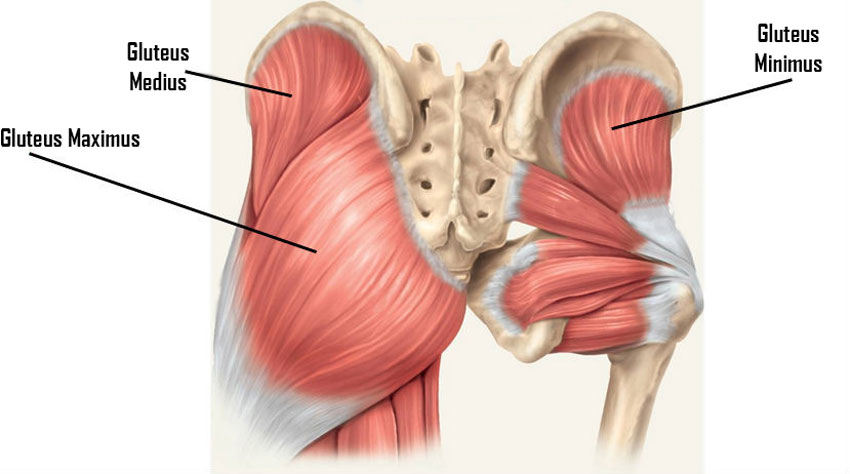

The glute muscles include the powerhouse gluteus maximus (max) and the stabilizing minimus (min) and medius (med).

When cycling, the glute max is involved with extending the hip along with the hamstrings. The glute med and min are important stabilizers that help keep your leg tracking evenly throughout the pedal stroke.

The glute max is active for almost the entire duration of the push phase of the pedal stroke, with most of the power coming in the first half as the hip opens.

It contributes roughly 30% of the power you generate on the bike. The contribution of the glute is higher in road cycling with a correctly fit bike.

The more aggressive the position (like on a triathlon bike), the more power the glute can generate.

The two other glute muscles don’t generate much power while biking but help keep the knee in a safe position.

As a result, a weak glute medius is often one of the first issues physiotherapists look for when treating lateral knee pain like IT band syndrome.

Strengthening the glutes so you can generate more power and maintain a stable pedal stroke is one of the most effective ways of improving your cycling performance and preventing injuries on the bike.

Lower Legs

Professional cyclist Janez Brajkovic’s calf muscles after a race.

The calf and shin muscles also play a big part in cycling, activating at the end of the power phase and continuing through the upstroke.

The calves comprise the small soleus, closer to the ankle, and the larger gastrocnemius medialis and lateralis.

The primary muscle in the front of the lower leg is the tibialis anterior. These muscles flex the ankle and knee.

The lower leg muscles contribute roughly 20% of your power on the bike.

The gastrocnemius is the biggest mover in the lower leg and is active for the middle half of the pedal stroke from 3 to 9 o’clock.

The soleus activates briefly midway through the push phase, and the tibialis anterior comes into play as the toes pull upwards in the last quarter of the pedal stroke.

The calf muscles become quite tight from cycling and benefit from post-ride stretching. Additionally, they will strengthen from the secondary activation required during exercises like squats and lunges.

Abdominals and Upper Body Muscles

Many curious cyclists ask, “does biking work abs?” and the honest answer is, not really.

The abdominal and upper body muscles mainly act as support and stabilizers for cycling, building a small amount of muscular endurance from supporting weight but developing very little strength.

A strong core plays a huge role in the recruitment of power from the rest of the body. In addition, abdominal endurance will help protect your spine during long days in the saddle and help you maintain proper posture while riding.

The exception to this is mountain biking and road cycling sprinters.

Doing crunches and planks can do wonders for your cycling performance and overall health.

Off-road disciplines require more strength in the upper body. This strength allows you to leverage and manipulate the bike over obstacles.

Likewise, sprinters need the ability to pull heavily against the handlebars during their sprints, requiring a lot of upper back, lats, tricep, shoulder, and abdominal strength.

Core and upper body exercises, done correctly, are an excellent way to improve your overall health and reduce the risk of injury on and off the bike.

Similarly, upper body stretches for spinal and shoulder mobility can help balance out the static nature of cycling.

What Muscles Does Stationary Cycling Work?

Indoor cycling is a great way to tone muscles, lose weight, and improve overall health and fitness, but it should be complemented by outdoor cycling. | Image source: trainingpeaks.com

Stationary cycling works the same primary muscle groups as outdoor riding.

However, indoor cycling excludes the small stabilizing muscles because balance isn’t required on an indoor bike. For this reason, it’s best to mix indoor and outdoor cycling.

Many modern indoor spin classes introduce upper body exercises into the session to create a full-body cycling workout. They do this by continuing to ride but doing things like biceps curls with small weights while spinning lightly.

What Muscles Does Biking Work vs. Running?

The muscles used for cycling vs. running are almost identical and include all of the lower body muscles. However, running requires a more active core and is generally more taxing on the cardiovascular system, producing a high heart rate and requiring more oxygen.

The percentage of power generated by each muscle is also quite different between the activities, with running requiring more glute and hamstring strength.

6 Best Strength Exercises for Cycling

As mentioned throughout the article, strength training for cyclists can help prevent injuries, enhance cycling performance, and improve overall health.

In this section, we will focus on activities that target the lower body and core.

Nonetheless, you should include upper body exercises into your strength sessions as well to ensure a balanced body and avoid overtraining a specific muscle group.

General Tips for Doing Any Strength Exercise

- Start with bodyweight and progress to weighted exercises as you build strength and master technique. Cyclists can derive tremendous benefits from simple bodyweight exercises.

- Focus on contracting the muscle(s) the exercise targets to get the best results.

- Engage your core to protect your spine and perform repetitions in a slow and controlled manner.

- Do as many repetitions as is necessary to fatigue the muscle you’re targeting. However, don’t continue an exercise with poor technique just to finish the set.

- Avoid going into a position you aren’t flexible enough to get into safely, for example, a butt-to-heel squat.

- Practice technique with the help of a personal trainer or by recording yourself. It’s essential to identify and correct mistakes in your form. Online instructionals can help with this.

Squats

Squats are one of the most effective exercises for developing the main power muscles for cycling, the glutes, and quads.

In addition, a squat will directly work the soleus and indirectly work the hamstrings, gluteus medius, gastrocnemius, and core muscles.

For most people, a high volume of bodyweight squats is enough to build strength and muscular endurance for cycling.

Once you are proficient at the squat technique, you can begin to add weight in the form of a bar or kettlebell to challenge yourself further.

- Sets: 3-4

- Repetitions: 10+

Walking Lunges

Lunges are another great exercise that primarily strengthens the calves, glutes, and quads, using the hamstrings as stabilizers.

Walking lunges also partially isolate each leg to reduce imbalances from favoring one side. The one-legged nature of this exercise also requires a lot of balance and core stability.

Lunges are another excellent bodyweight exercise, but you can also do them by carrying dumbbells or kettlebells to add resistance.

- Sets: 3-4

- Repetitions: 10+ each leg

Wall Sits

Wall sits work the quads, glutes, hamstrings, and inner/outer thigh muscles.

They are an excellent method of building muscular endurance in the primary muscles for cycling, making them one of the most popular and accessible exercises for cyclists.

Muscular endurance is your muscle’s ability to perform work for an extended period. This training increases your muscles’ time to exhaustion, such as when climbing out of the saddle.

- Sets: 3-4

- Duration: Until fatigue

Straight Arm Plank

The plank is one of the most common strength exercises. It’s a standalone exercise and the beginning position for others like pushups and mountain climbers.

A straight arm plank is an excellent full-body exercise, building muscular endurance across the body, with a primary focus on the abdominals and the glutes, but also working the erector spinae.

Plank is hugely beneficial when done correctly but ineffective if done poorly, so avoid common mistakes. To maximize the effect, squeeze your hands and feet together and notice the difficulty increase.

- Sets: 3-4

- Duration: Until fatigue

In addition to this, you can also do side planks for the obliques, to really round up your core strength and stability.

Single-Leg Deadlifts

The deadlift is one of the most beneficial exercises for strengthening the hamstrings and gluteal muscles and preventing lower back pain.

A single-leg deadlift has the additional benefit of challenging all of the muscles in the core, legs, and feet with stability. By doing them correctly and contracting your latissimus dorsi muscles, you can also work your back.

The hamstrings are an often-neglected muscle group by cyclists, so adding deadlifts to your routine will help balance your leg strength.

- Sets: 3-4

- Repetitions: 10+ each leg

Banded Glute Bridges

Banded glute bridges are one of the most effective ways of isolating the glute max and med to improve muscular endurance and strength while strengthening the abdominals.

You can do variations of this exercise that hold at the top, squeezing the glutes to focus on endurance or lowering and raising the glutes to focus on power.

A massive benefit of doing bridges with a band is training the glute medius to alleviate or prevent Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS), one of the most common cycling injuries.

- Sets: 3-4

- Repetitions: 10+ or hold until fatigue

5 Best Stretches for the Muscles Used During Cycling

Stretching is an often overlooked but essential part of maintaining a healthy body, especially for cyclists.

Cycling is a unique endurance sport in that most of the time is spent in a static position, resulting in a shortening of various muscle groups.

Stiff muscles can limit our ability to perform simple tasks and contribute to muscular imbalances and injuries.

Given that, stretching can help prevent injury and improve performance on the bike and general wellbeing.

Static vs. Dynamic Stretching

Stretching before a ride is helpful, as long as it is a ‘dynamic’ stretching routine. A short, active flow helps wake up the muscles and joints for better activation on the bike.

Post-ride stretching can help address the stiffness built up over time on the bike.

Static stretching involves longer holds with steady, deep breathing. This teaches the muscles to relax, release tension, and restore length.

This section will focus on post-ride stretches for cycling. Try holding each one for one to two minutes, breathing steadily to relax the body.

Pidgeon or Figure-Four

The pigeon stretch is hugely beneficial for cyclists as it targets the front and back hip muscles, lower back, quads, and inner thigh.

These muscles are heavily involved with cycling and become stiff from hours spent on the bike and sitting throughout the day.

Figure four is a regressed variation of the pigeon stretch for those who are limited in their flexibility or experience knee pain during pigeon.

Quad Couch Stretch

The couch stretch or yoga’s low-lunge pose is the best stretch for cyclists as it opens up the anterior (front) hip and quads, which shorten while cycling.

Chronically shortened hip flexors and quads can quickly contribute to lower back and knee pain.

This stretch is doubly beneficial for those who spend long durations seated throughout the day with the hip in a closed position.

Cat-Cow

Cat-cow is one of the most common stretches thanks to its relative simplicity and utility for spinal warm-up or spinal mobility.

The spine is in a relatively consistent position while cycling, which can lead to stiffness in a specific area, depending on where you are naturally flexible.

Cat-cow focuses on bending each vertebra sequentially to release tension and stiffness, allowing you to enter your riding position more comfortably the next time you ride.

Downward Dog

Downward Dog is one of the best stretches you can do after riding. It opens up tight hamstrings and calves along with the shoulders and chest.

It is quite an active stretch that builds strength in the arms, especially in the triceps, and requires concentration on each limb and engaging the core to maximize the benefits.

Cyclists often struggle with hamstring and calf flexibility as the riding position keeps the two muscles in a limited range of motion.

Likewise, while riding, the chest is in a closed position, and the shoulders are slightly extended, making Downward Dog doubly beneficial as it reverses this.

Wide-Legged Forward Fold

A wide-legged forward fold is another great stretch for the adductors and hamstrings that involves some activity in the quads and core.

Adductors on the inner thigh, like the hamstrings, become tight from sitting and the repetitive motion of cycling.

This pose can help alleviate the tension in these areas while building strength in the core. It’s also easy to modify if you’re stiff.